Knowledge Center

Knowledge Center

Quarterly Newsletter – Q3 2021

Market Commentary

US equities notched a small positive return in Q3. Strong earnings had lifted stocks in a run up to August, but jitters over growth and inflation concerns late in the quarter meant US equities retraced their steps in September. September has historically tended to be the weakest month of the year, and this year it marked the first decline of 5% or more from market tops since October 2020. US 10-year Treasury yields jumped to the highest level in three months, spooking some investors. We are encouraged by the market’s relative resilience in the face of negative seasonality and a lengthy list of investor worries.

Economy Peaking

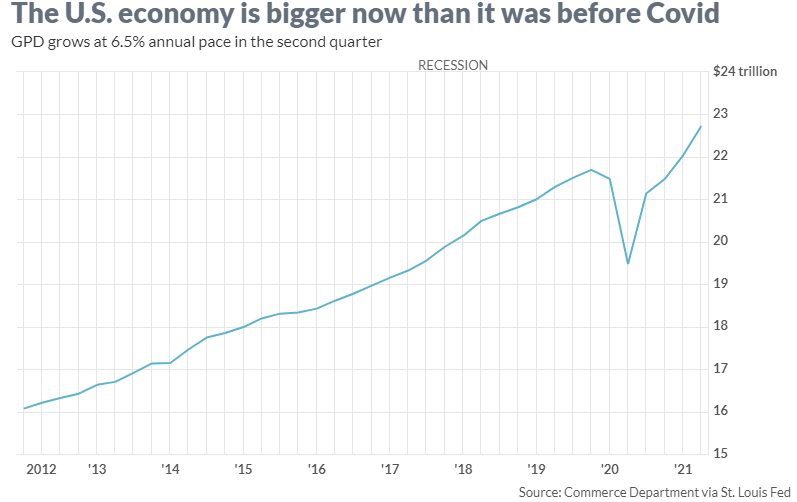

The US economy grew rapidly in the spring, with the reopening of businesses, incremental government relief, and healthy consumers fueling a swift recovery. Gross domestic product, the official scorecard for the economy, expanded at a 6.5% annual pace in the second quarter, and has now exceeded pre-pandemic levels after the short but deep recession last year.

Economic data remain strong, but early indicators suggest the recovery may be slowing down from the rapid pace of early summer. That burst of economic growth – driven by rounds of stimulus and a surge in consumer spending as the economy reopened – is fading, and we are heading into a more moderate phase of expansion. This is not surprising; the economy can’t grow at a 6-8% rate indefinitely. Over time, we expect a gradual reversion to the mean for an economy more used to growing closer to 2%.

Several factors, including the emergence of the Delta variant of Covid, labor mismatches, supply shortages, and transport bottlenecks have limited and slowed economic activity. Even as these headwinds have detracted from the pace of growth, we believe the economy’s trajectory remains positive. Demand for goods has not been permanently destroyed, and in many cases we expect that what was in tight supply in 2021 will likely be consumed in 2022 and 2023. Autos, currently hampered in availability from wide-scale chip shortages, are a prime example.

Supply Chain Woes

Covid continues to impact the global supply chain. Dislocations are present everywhere; from the container market, to shipping routes, ports, air cargo, trucking lines, railways and even warehouses. In August, China shuttered a key terminal at its Ningbo-Zhoushan port, the world’s third-busiest port, for two weeks due to a single Covid-19 case. A disruption of this magnitude led to a cascading effect down the supply chain, with the backlog stretching across the Pacific Ocean to the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, which together handle about one-third of all containers coming into the US. The result has created shortages of key manufacturing components, order backlogs, delivery delays, and a spike in transportation costs and consumer prices.

Manufacturing slowed into the back half of the quarter, reflecting the ongoing challenges to the supply chain and materials and labor shortages. Delivery times lengthened substantially as transportation challenges and shortages led to one of the greatest deteriorations in vendor performance on record. Complications within global supply chains are lasting longer than anticipated as we continue to battle the surge in the Delta variant.

Part of the issue, too, is that supply chains are overloaded by a sudden surge in consumer demand. Strong demand is not a bad thing; it will be a lot more worrying if demand is not there. Household savings have risen by $4.3 trillion since the beginning of 2020 to a record $17 trillion, driven by government pandemic aid and higher wages. US jobs openings have moved to a record high, and workers are starting to return to the workforce as the federal unemployment benefits come to an end. Optimism is high among manufacturers and purchasing managers as they stand eager to take advantage of strong demand opportunities once conditions start to improve. Encouragingly, businesses have been investing heavily in equipment, software, and R&D, which has the potential to boost productivity rates in future years.

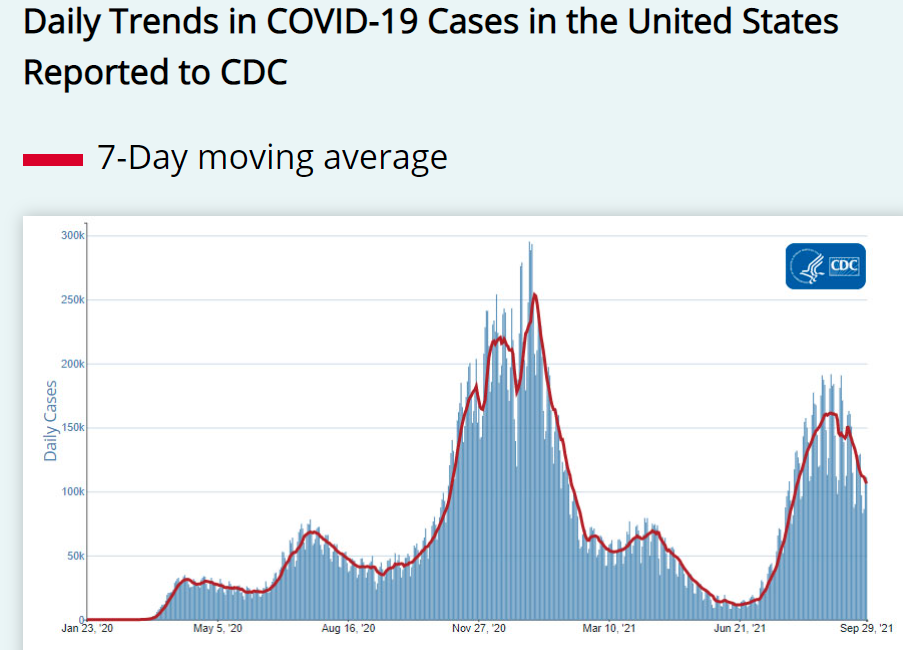

In order for the supply lock-up to start easing up, the situation surrounding Covid needs to get better first. It is worth nothing that supply constraints were actually showing signs of improvement in late spring and early summer. The rapid spread of the delta variant around the same time quickly put a halt to the progress. Tracking data from the CDC, we are seeing a clear downtrend in the number of new cases and deaths in the US. Worldwide, cases have also dropped more than 30% since late August. The decline is consistent with past patterns, where cases often surged for about two months in new regions before starting to level off. Covid is unlikely to disappear anytime soon, and will continue to circulate for years. But for now, with higher vaccination rates and the development of new therapeutics (such as the new antiviral pill launched by Merck), we are hopeful that the worst of the pandemic is behind us.

Inflation Remains Elevated

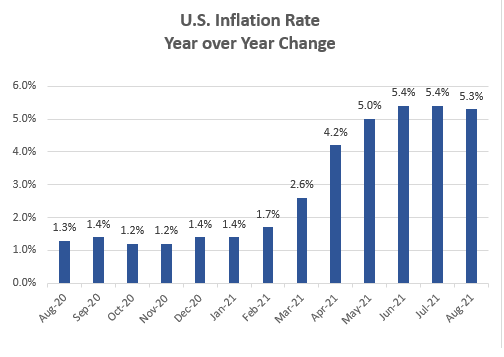

Inflation isn’t something we have had to contend with in the last few decades. The average annual increase in inflation for the last ten years has been less than 2.0%. As our economy reopened from the self-imposed countrywide shut-down, the subsequent unleashing of the pent-up consumer demand combined with the supply and labor shortages have driven inflation to its hottest pace in 30 years. Over the summer, we have seen price surges in used cars, lumber, food, and gasoline. Some price increases have moderated, but others have not fully. A runaway inflation can erode household-spending power, and can be especially concerning for everyday folks and policymakers if allowed to spread unchecked.

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose 5.3% in August from a year earlier, and 0.3% over the past month. When we remove the volatile food and energy prices (so-called core CPI Inflation), the picture was somewhat better. Prices rose by just 0.1% for the month, the smallest increase in six months and the second straight month in which the inflation rate fell slightly. Gasoline and food prices continue to move higher, but used car prices, along with travel-related expenses, fell. While we believe that inflation pressures will likely persists for a while longer and some degree of permanence to inflation relative to pre-pandemic levels, we continue to believe that most of the upward pressure on prices should subside once supply chain woes ease.

Fed Tapering

Since 1977, the Federal Reserve has operated under a dual mandate from Congress to conduct the nation’s monetary policy consistent with promoting the goals of maximum employment and stable prices. With inflation rising, investors are anticipating the Fed’s next policy pivot. In a normal environment, rising inflation would be countered by the Fed by raising interest rates to cool demand.

Statements from the Fed meeting in September reflected that the Committee is close to announcing a tapering of the bond purchases that have been in place since the early days of the pandemic. To refresh, the Federal Reserve cut interest rates down to zero, and initiated a program to buy $120 billion of bonds ($80 billion in Treasury, and $40 billion in mortgage-backed securities) monthly to alleviate fears and provide liquidity to the market.

As inflationary pressures continue to weigh on the economy, debate arises on when the Fed should start withdrawing some of its monetary support sooner than previously guided. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell recently indicated that the economy has reached a point where it no longer needs as much policy support, and it is likely the central bank will begin tapering some of its easy money policies before year end. “Tapering” refers to the process of reducing the amount of asset purchases over time, and is most likely a precursor to rising rates.

The Federal Reserve will be under intense scrutiny as it moves toward tighter monetary policy, and walking the very fine line between keeping the economic recovery on track and controlling inflation. Even without the Fed withdrawing its support, there are a number of headwinds that could knock the fragile recovery off course, including a deadlock over the debt ceiling, the continued spread of Covid, and peaking economic growth. With markets so accustomed to quantitative easing and low rates, volatility may rise as investors grow wary of a misstep in timing.

Political Standoff

The standoff in Washington over a variety of issues continues, with the debt ceiling at the top of investors’ minds. The US hit its debt limit on August 1st, which means the Federal government cannot increase the amount of outstanding debt. Therefore, it can only draw from any cash on hand and spend its incoming revenues to fund its liabilities and operations. The Treasury also took certain “extraordinary measures” through the creative manipulation of accounting methods to extend how long it can continue to pay all the government’s obligations while staying below the limit. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has stated that the government will likely run out of extraordinary measures if Congress does not raise or suspend the debt limit by October 18th. As of writing, the House of Representatives approved a legislation to raise the debt limit, allowing the Treasury Department to keep debt payments flowing until early December. The bill now travels to President Joe Biden’s desk for his signature and enactment.

The debt ceiling has, in the past, spurred contentious and prolonged debate about fiscal responsibility and the growing national debt. If the debt ceiling is not raised or suspended again before that time, the Treasury would be unable to issue more Treasury securities, and the nation could in theory default on its debt.

Failing to increase the debt limit would have catastrophic economic consequences. It would cause the government to default on its legal obligations, an unprecedented event in American history. The full faith and credit of the US would be permanently impaired, and could result in a potential downgrade of the U.S’s AAA credit rating. It would precipitate another financial crisis, and would almost certainly put the US right back in a deep economic hole, just as the country is recovering from the recent recession.

History suggests that is unlikely. Congress has always acted to forestall default, though often at the last possible minute. In fact, since 1960, Congress has acted 78 separate times to permanently raise, temporarily extend, or revise the definition of the debt limit. It is important to recognize that raising the debt limit does not authorize new spending. It simply allows the government to continue to issue Treasuries to finance legal obligations already committed. Political uncertainty, especially over such an important headliner, can cause some short-term market volatility, but we do not anticipate this to turn into a long-lasting issue.

Outlook

As noted, the market has been a bit soft for the last few weeks. Investors have had much to worry about, and the recovery story is far more nuanced than earlier in the year. We remain constructive on a longer-term view of the recovery,

In the short term, we think there is elevated risk for some additional market weakness, and we are looking to the upcoming earnings reporting season for clues to investor sentiment. Unlike the second quarter’s pervasive “good news” earnings stories, we expect the third quarter to show the impact to companies’ bottom lines lower sales volumes (often due to the lack of merchandise to sell, as in the case of autos and retail) and higher input costs from goods inflation, transportation, and energy. Tight labor markets, and building cost pressures there, do not help matters. Last but not least, interest rates are moving higher (though off low absolute levels), and inflation break-even spreads are nearing their high levels from the springtime.